Who was Alice Billing?

The building was named after Alice Billing in the 1990s, a pioneering local sanitary inspector and one of the first women to hold such a role nationally.

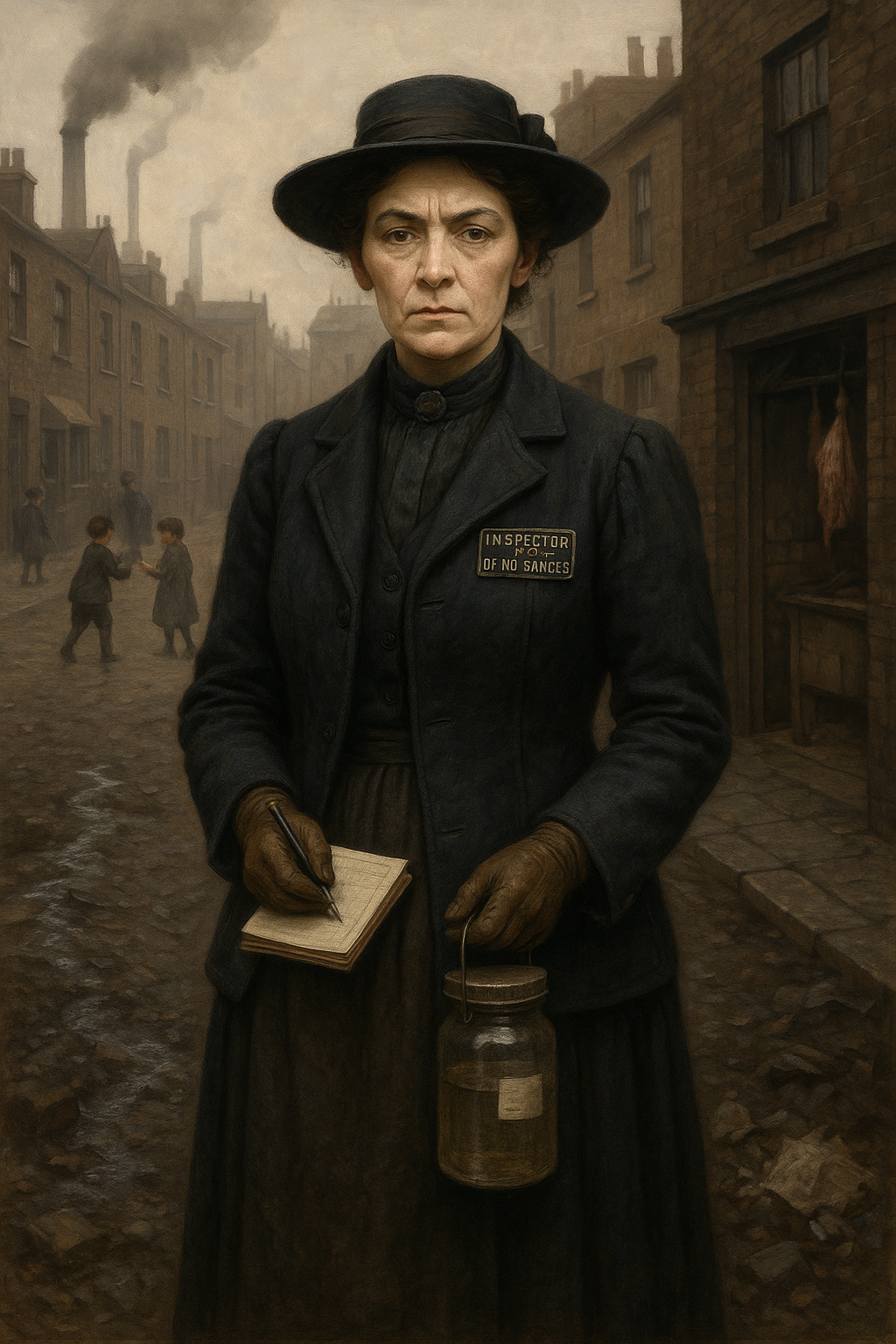

Her story was largely unknown, so in 2025, as part of a Newham Heritage Month, we created and delivered a project called Inspector of Nuisances to uncover narratives from both history and the present.

The Research

The first phase of the project involved commissioning local genealogist and historian Kathleen Charter to trace the Billing family and explore Alice Billing’s role as a sanitary inspector in 19th-century West Ham.

This research built upon earlier work by local historian Mark Gorman, who had already begun uncovering Alice’s story and her historical context.

What follows is a condensed version of the research compiled by the duo. Their work laid the foundation for a trilogy of workshops designed and facilitated by Frames of Mind, which explored changing attitudes toward women’s health and working conditions in Newham over the past sixty years, drawing inspiration from the pioneering work of Alice Billing.

Alice Billing - Family Background

1837 John Billing born. He came to London in 1861 and married Martha Barnes. Profession - Cooper (barrel maker)

1864: first surviving child with Martha, Emmeline Billing, born.

1867: Alice Sarah Billing, born 27th July, at Nelson Terrace, Limehouse.

Alice never married, but her sister married a musician, Samuel Dalladay, in Emmanuel Church, Forest Gate.

1891 census tells us that they were living in Lauriston Road, Hackney, and Alice lived with them. They were able to employ a servant.

1897 Alice Billing qualified as a Sanitary Inspector c.1897 at the Royal Sanitary Institute in Kensington.

1898 John Billing died

1901 census: Alice, 29, lives in 10 Lancaster Road, E7, with her widowed mother and a lodger.

1911 census Alice, 39, still lives at 10 Lancaster Road.

25 December 1948, Alice died, aged 76. She was still living at 10 Lancaster Road and was buried 6 days later in Manor Park Cemetery. [Square 273 - Number 97240].

Borough of West Ham Background

West Ham’s proximity to the Thames and River Lea provided strong transport links that attracted diverse industries. Early on, flour milling and market gardening thrived. The area became a hub for shipbuilding with the establishment of Thames Ironworks in 1857, which later inspired the founding of West Ham United football club. The expansion of railways in the 1840s further integrated West Ham into London’s industrial fabric.

Following the 1844 Metropolitan Buildings Act, many polluting industries relocated to West Ham. Major businesses emerged, including the India Rubber and Telegraph Works in Silvertown, Tate & Lyle sugar refineries, and James Keiller’s jam factory. The opening of the Royal Docks (1855–1921) solidified the area's role in international trade, particularly for raw materials.

Southern West Ham became heavily industrial, while the north developed residential areas. The district also hosted notable factories like Knight’s Soap Works, Loders & Nucoline (makers of early vegan margarine), and Yardley’s perfumery. Some industries, like Crockett’s Leathercloth, were located inland.

By the early 20th century, many companies were absorbed into larger firms like Unilever. The area's economic and demographic growth led to its recognition as a parliamentary borough in 1885 and a municipal borough in 1886.

Sanitary inspectors, aka Inspectors of Nuisance, suddenly became a vital role in protecting public health during this time of rapid industrial growth and urban overcrowding. As cities became densely populated and polluted with waste from factories and homes, inspectors were responsible for identifying and reporting unsanitary conditions such as overflowing cesspits, contaminated water, and overcrowded housing.

Following public health legislation like the 1848 and 1875 Public Health Acts, they were empowered to enforce hygiene standards by issuing legal notices, ordering repairs, and shutting down unsafe premises. Their work was especially critical during outbreaks of diseases like cholera and typhoid, helping to prevent their spread. In some areas, they also educated the public about hygiene and sanitation, laying the foundation for modern public health systems.

Position of Women in West Ham

When West Ham County Borough was formed, all councillors were male. Edith Kerrison became the first female councillor in 1917. A former nurse and matron, she was active in socialist causes and children’s education, and later served on key local committees. Despite social norms requiring women in public roles to resign upon marriage, many working-class women continued to work out of necessity, often from home.

Daisy Parsons, West Ham’s first female mayor, was a suffragette and councillor who balanced activism with family life. Her husband’s support was instrumental to her success.

Alice Billing was another notable figure, appointed to the rare independent position as Inspector of Nuisances and would have witnessed the struggles of many women firsthand.

During both World Wars, women stepped into industrial roles, boiling sugar and operating packing machinery at companies like Tate & Lyle. Though women gained voting rights gradually from 1869 onwards, full suffrage and legal pay equality came much later, with the Equal Pay Act not arriving until 1970.

Alice Billing – Applying for the Role of Sanitary Inspector

At the start of 1893, London had 115 sanitary inspectors, all of them men. But within just a few years, this began to change. As growing concern arose about working conditions for women and girls, several boroughs began employing female sanitary inspectors. West Ham was one of the first to take this progressive step.

In 1897, Alice Billing qualified as a Sanitary Inspector through the Royal Sanitary Institute in Kensington, a significant achievement for a woman at the time.

The following year, in 1898, she was selected as one of three candidates for the newly created post of "Woman Assistant Inspector" by West Ham Council’s Public Health Committee. While she stated her age as 28, records show she was actually 32.

Why Were Women Sanitary Inspectors Needed?

“No man could possibly supervise the sanitary arrangements for the vast army of women and girl workers in factories, and it was notorious, among those in the know, that many of these poor creatures would put up silently with unhealthy surroundings rather than carry their grievances to the male official.”

Daily News (London), 27 December 1902

There was a growing recognition that women workers needed inspectors who could relate to their circumstances, someone they could trust and speak to openly. Women inspectors were better positioned to address the unique health and hygiene issues faced by female workers, particularly in environments where men were not permitted or where women felt too intimidated to speak up.

What Made a Good Female Sanitary Inspector?

A successful applicant needed a specific blend of personal qualities and physical stamina:

“It is essential that the applicant should be thoroughly healthy, a good walker, and fond of outdoor life... Above all, the would-be inspector should have quick observation and full measure of tact and judgment, for she has to deal with human beings, and in many a case she has to visit will require womanly sympathy and discrimination... She will have counsel to give, abuses to investigate, remedies to suggest, and the more tactfully this is done, the more valuable will she be.”

The hours were demanding, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily, with Saturdays as half-days, and the job required regular walking and inspections in all weather conditions.

Salary and Recognition

The role came with relatively strong pay for a woman at the time:

Sanitary Inspectors earned between £80 and £150 per year

Applicants had to be between the ages of 25 and 40

In 1900, Alice Billing, by then an Assistant Inspector, applied for a salary increase. She was recommended for a raise from £90 to £110, with incremental increases up to a maximum of £140.

For comparison, the lowest-paid junior male inspectors were awarded a rise from £120 to £135 (West Ham Committee Reports, 1899–1900, Vol. XIV).

Alice Billing - Her Work

Sanitation, Public Health, and the Work of Alice Billing in West Ham

By the mid-19th century, the role of the Inspector of Nuisances became central to tackling dangerous and offensive conditions affecting public health. This included overseeing industrial smells, boiling bones, accumulations of filth, effluvia from privies, contaminated basements, drains, refuse heaps, and offensive trades such as abattoirs. In growing urban areas like Canning Town, where open sewers were common, these issues were especially severe.

Expanding Responsibilities: Housing, Food, and Disease

As industrialisation progressed and urban slums expanded, inspectors’ responsibilities widened. Initially focused on housing conditions, their scope grew to include food adulteration, which became a major public concern in the 19th century. They were required to understand a range of legislation relating to housing, food safety, and disease control, as evident in the training materials and examination requirements of the time.

PICTURE: milk delivery cart 1917

Many common foodstuffs were dangerously adulterated. For example:

Flour was often bulked out with alum

Tea could be diluted with other leaves

Milk was frequently watered down and sometimes came from sick cows, which could transmit tuberculosis

Meat used in pies might come from diseased or stray animals—including, it was rumoured, even dogs or cats

Lead was added to some foods to enhance colour

The Sale of Food and Drugs Act (1875) aimed to curb such practices, but poor-quality and unhygienically prepared food remained a persistent problem.

Public Health and Infectious Disease

Sanitary inspectors were also charged with reporting outbreaks of numerous infectious diseases. These included smallpox, cholera, diphtheria, scarlet fever (scarlatina), typhoid, puerperal fever, membranous croup, erysipelas, and a range of "fevers" such as relapsing fever (malaria), continued fever, and enteric fever. Householders or general practitioners who failed to report cases could be fined up to forty shillings.

The arrival of overseas visitors and seamen through the London docks introduced rarer diseases into the area. This led to the establishment of the Seamen’s Hospital at Custom House in 1890, and later the founding of the London School of Tropical Medicine at the same site in 1899 (before its move to central London in 1924).

The Role of Women: Alice Billing’s Pioneering Work

Alice was deeply involved in frontline inspection and enforcement, in her role as West Ham’s first female Sanitary Inspector, and made a significant and lasting impact on local public health. Her 1899 records alone illustrate her commitment and productivity:

Inspected over 500 premises where women were employed

Identified and reviewed 793 domestic workshops, primarily in clothing, but also in match-making, paper bag production, and slipper/mattress making

Discovered and addressed 1,036 public health nuisances, including filthy conditions, defective drains, faulty lavatories, and unsafe staircases

Conducted nearly 1,000 inspections of milk shops, resulting in over 700 documented issues and more than 100 official Notices served

Issued a total of 198 Notices across her inspections

Her work challenged assumptions about women’s capabilities in public service and health enforcement.

Recognition and Legacy

Alice Billing’s influence was so valued that in December 1899, West Ham Borough Council appointed two additional women sanitary inspectors, making it a local authority with a pioneering number of women in these roles. A 1902 report in the Woodford Times noted:

“Some time ago, the Borough Council at West Ham appointed a lady sanitary inspector. They were so pleased with her work that after a time they appointed a second and again a third. I believe that no Borough in England has as many lady sanitary inspectors. It is in this way, by doing really excellent work quietly, and showing common sense, that all the prejudice that exists against any further widening of women's sphere will be swept away.”

– Woodford Times, 10th January 1902

Though the names of inspectors were often omitted from court records, likely to protect them from reprisal, their role was both vital and transformative. In particular, Alice Billing’s legacy highlights how women, even when under-documented, helped lay the groundwork for modern public health systems through resilience, diligence, and common sense.

What the Historians said about their experience of researching Alice Billing

Kathleen Carter, Local Historian and Genealogist, said:

“I found researching Alice very interesting. It's a fascinating period as at this time ordinary women were beginning to start the (long) process of gaining better opportunities and status. The borough of West Ham, now incorporated into Newham, was progressive, and I encountered other trail-blazing women like Alice while researching her. She was not alone and her story will, I hope, inspire other people to find out more about this exciting time and place.’

Mark Gorman, Local Historian, said:

"Researching the life and work of Alice Billing has been both fascinating and frustrating. Fascinating because Alice was a pioneering figure in East London, as the first woman to work in public health locally, making a contribution which was remembered 50 years after her retirement by a building named after her. Frustrating because we know too little, either about her professional activities or her life outside work. However, that's often the way with local history, and I've enjoyed every minute of the search for information. And the quest goes on!"